Interview with the Creators of Hoaxy® from Indiana University

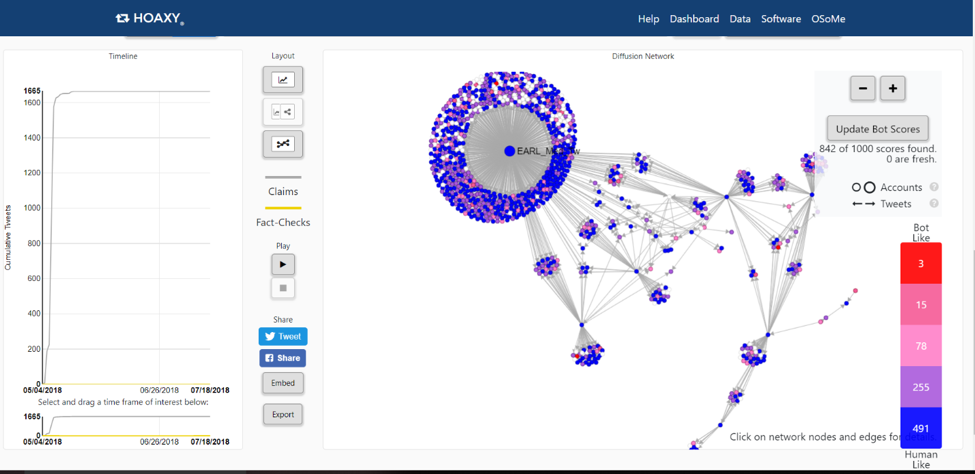

Figure 1. A Hoaxy® diffusion network regarding claims about the HPV vaccine.

Falsehoods are spread due to biases in the brain, society, and computer algorithms (Ciampaglia & Menczer, 2018). A combined problem is “information overload and limited attention contribute to a degradation of the market’s discriminative power” (Qiu, Oliveira, Shirazi, Flammini, & Menczer, 2017). Falsehoods spread quickly in the US through social media because this has become Americans’ preferred way to read the news (59%) in the 21st century (Mitchell, Gottfried, Barthel, & Sheer, 2016). While a mature critical reader may recognize a hoax disguised as news, there are those who share it intentionally. A 2016 US poll revealed that 23% of American adults had shared misinformation unwittingly or on purpose; this poll reported high to moderate confidence in one’s ability to identify fake news with only 15% not very confident (Barthel, Mitchell, & Holcomb, 2016).

What’s the big deal?

The Brookings Institute warned how organized disinformation campaigns are especially dangerous for a democracy: “This information can distort election campaigns, affect public perceptions, or shape human emotions” (West, 2017). Hoaxes are being revealed through fact-checking sites such as FactCheck.org, Politifact.com, Snopes.com, and TruthorFiction.com. These have the potential to reveal falsehoods and provide any corresponding truth in the details or alternative facts. For example, PolitiFact’s Truth-O-Meter is run by the editors of The Tampa Bay Times. This tool was so crucial for checking the veracity of candidates’ statements during the 2008 Presidential campaign season that they won a Pulitzer Prize for Journalism in 2009.

Hoaxy® (beta)

Hoaxy® takes it one step further and shows you who is spreading or debunking a hoax or disinformation on Twitter. It was developed by Indiana University Network Science Institute and the Center for Complex Networks and Systems Research. The Knight Prototype grant and the Democracy Fund support it. The visuospatial interactive maps it produces are called diffusion networks and provide real-time data if you grant the program access to your Twitter account. Hoax purveyors be warned—it shows the actual Twitter user or Bot promoting it through grey, low-credibility claims. Conversely, it also displays in yellow the Twitter accounts fact-checking the claim.

Bots are determined by computer algorithms and given a score based on the science behind the Botometer with red identifying accounts most ‘Bot Like’ and blue for most ‘Human-Like’. The website’s landing page provides trending news, popular claims, popular fact-checks, and a search box for queries. The site’s Dashboard shows a list of influential Twitter accounts and number of tweets for those sharing claims or fact-checking articles with the corresponding Botometer Score.

Use Hoaxy® to find out who is at the center of a hoax by clicking the node to reveal the Twitter account. It’s also interesting to see who the outliers are and their six degrees of separation. Select a node, and it will provide the Botometer Score and whether they quoted someone or someone quoted them (retweets) on Twitter. For example, a magician named Earl is the approximate epicenter for spreading misinformation about the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine causing an increase of cervical cancer in Swedish girls. See vaccine query visualized on Hoaxy, as in Figure 1. Based on the sharing of the article from Yournewswire.com, it had 1665 people claiming it and zero disclaimers on Twitter, as of 7/18/18. As for the facts, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, HPV vaccines are safe and prevent cervical cancer (2018).

It was a privilege to talk to the Hoaxy project coordinator, Dr. Giovanni Ciampaglia, on behalf of his co-coordinators Drs. Alessandro Flammini and Filippo Menczer:

What was the inspiration or tipping point to invent Hoaxy®?

We started Hoaxy because we could not find a good tool that would let us track the spread of misinformation on social media. The main inspiration was a project called Emergent (emergent.info), which was a really cool attempt at tracking rumors spreading through the news media. However, it was a completely manual effort by a group of journalists, and it was hard to scale to social media, where there are just so many stories published at once. So, we set out with the idea in mind of building a platform that would work in a completely automated fashion.

Since its creation in 2016, what are some of the overhauls that the Hoaxy® software program required for updates?

Hoaxy has evolved quite a bit since we first launched in 2016. The main overhaul was a complete redesign of its interface, during which we also integrated our social bot detection classifier called Botometer. In this way, Hoaxy can be used to understand the role and impact of social bots in the spread of both misinformation, and of low-credibility content in general.

What are some of the unexpected uses of Hoaxy?

We were not entirely expecting it when we first heard it, but several educators use Hoaxy in their classrooms to teach about social media literacy. This is of course really exciting for us because it shows the importance of teaching these skills and of using interactive, computational techniques for doing so.

What hoax is currently fact-checked the most?

Hoaxes are constantly changing, so it’s hard to keep track of what is most fact-checked hoax. However, Hoaxy shows what fact-checks have been shared the most in the past 30 days, which gives you an idea of the type of hoaxes that are circulating on social media at any given time.

What’s the most absurd claim you encountered?

There are just too many… my favorite ones have to do with ancient prophecies and catastrophes (usually about asteroids and other astronomical objects).

Has Hoaxy® won any awards? (If not, what type of award categories does it fit in?)

It has not won an award (yet!). We are grateful however to the Knight Foundation Prototype Fund and to the Democracy Fund, who supported the work of integrating Botometer into Hoaxy.

I noted Mihai Avram’s (Indiana University graduate student) work on Fakey, a teaching app on discerning disinformation that is gamified. Are you involved with overseeing that project as well?

Yes, Filippo is involved in it. Mihai has also worked on Hoaxy; in fact, without him the current version of Hoaxy would have certainly not been possible!

What are some other resource projects your team is working on now?

Hoaxy is part of the Observatory on Social Media (osome.iuni.iu.edu), and we provide several other tools for open social media analytics (osome.iuni.iu.edu/tools). We are working on improving Hoaxy and making it operable with other tools. The ultimate goal would be to bring Hoaxy into the newsroom so that reporters can take advantage of it as part of their social media verification strategies.

What type of research is critically needed to better understand the spread of disinformation and its curtailing?

We definitely need to better understand the “demand” side of dis/misinformation — what makes people vulnerable to misinformation? The complex interplay between social, cognitive, and algorithmic vulnerabilities is not well understood at the moment. This will need a lot of investigation. We also need more collaboration between academia, industry, civil society, and policymakers. Platforms are starting to open up a little to partnering with outside researchers, and there will be much to learn on all sides.

Is there anything else you would like to share?

Yes! We are always happy to hear what users think about our tools, and how we can improve them. To contact us you can use email, Twitter, or our mailing list. More information here: http://osome.iuni.iu.edu/contact/

About Giovanni Ciampaglia

Dr. Ciampaglia is an assistant professor in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering at the University of South Florida. Previously, he was an assistant research scientist and postdoctoral fellow at the Indiana University Network Science Institute, where he collaborated on information diffusion with Drs. Menczer and Flammini and co-created Hoaxy. Prior to that, he was a research analyst contractor at the Wikimedia Foundation. He has a doctorate in Informatics from the University of Lugano in Switzerland. His research interest is in large-scale, collective, social phenomena on the Internet and other complex social phenomena such as the emergence of social norms.

Dr. Ciampaglia is an assistant professor in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering at the University of South Florida. Previously, he was an assistant research scientist and postdoctoral fellow at the Indiana University Network Science Institute, where he collaborated on information diffusion with Drs. Menczer and Flammini and co-created Hoaxy. Prior to that, he was a research analyst contractor at the Wikimedia Foundation. He has a doctorate in Informatics from the University of Lugano in Switzerland. His research interest is in large-scale, collective, social phenomena on the Internet and other complex social phenomena such as the emergence of social norms.

References

Barthel, M., Mitchell, A., & Holcomb, J. (December 2016). Many Americans believe fake news is sowing confusion. Trusts, Facts, & Democracy. Pew Research Center Journalism and Media. Retrieved from http://www.journalism.org/2016/12/15/many-americans-believe-fake-news-is-sowing-confusion/

Ciampaglia, G. L., & Menczer, F. (June 2018). Misinformation and biases infect social media, both intentionally and accidentally. The Conversation. Retrieved from http://theconversation.com/misinformation-and-biases-infect-social-media-both-intentionally-and-accidentally-97148

Mitchell, A., Gottfried, J., Barthel, M., & Shearer, E. (July 2016). The modern news consumer. Trusts, Facts, & Democracy. Pew Research Center Journalism and Media. Retrieved from http://www.journalism.org/2016/07/07/the-modern-news-consumer/

Qiu, X., Oliveira, D., Shirazi, S., Flammini, A., & Menczer, F. (2017). Limited individual attention and online virality of low-quality information. Nature Human Behavior, 1(132). doi:10.1038/s41562-017-0132

West, D. M. (2017). How to combat fake news and disinformation. The Brookings Institute. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/research/how-to-combat-fake-news-and-disinformation/?gclid=EAIaIQobChMI2eK5nbrA3AIVDgFpCh1k1wepEAAYASAAEgIL0PD_BwE