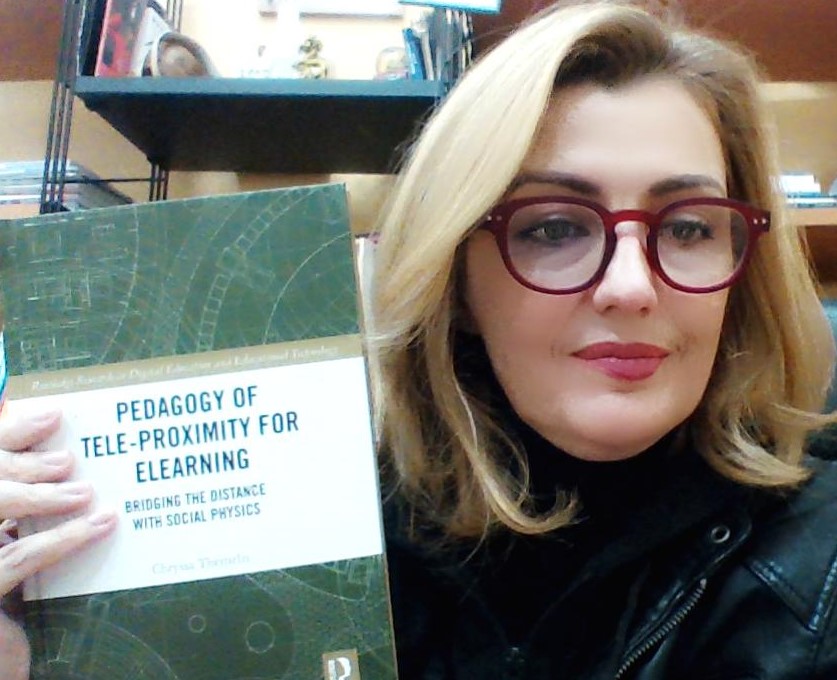

An Interview with Chryssa Themelis: ‘I see myself as a lifelong learner online in networked communities’.

Over the years, Chryssa Themelis has contributed various articles on diverse topics to AACE Review. This article summarizes significant themes of her work and concludes with an interview about her latest endeavor – a book about social physics, tele proximity and e-learning pedagogy. Chryssa defines tele-proximity as a paradigm that integrates learning theories, information technology, and visual media competencies from a Social Physics perspective. Social physics is an emerging field that uses mathematical patterns to understand collective human behavior for better performance, collaboration and creativity (Pentland,2014). Online learning and remote work are a reality for many people in the post-pandemic world and will be the mainstream working and learning pattern in the coming years. Pedagogies supporting tele-proximity can build a shared sense of place while interacting in virtual environments that minimize transactional distance and enhance collective intelligence and democracy.

One of Chryssa’s areas of expertise is how virtual spaces impact learners’ connectedness and wellbeing. For example, the project Digital Wellbeing Educators has a clear objective: increase the capacity of lecturers and teachers to integrate digital education in a way that promotes the digital wellbeing of students.

Another area of interest is inclusive visual learning – either learning from visual materials or learning by creating visual material. I recommend reviewing the CIELL project, which got the British Council ELTON award for digital innovation and inclusion in 2021. In this multimedia platform, learners engage with UN 17 sustainable goals as comics to understand essay writing. Then there are drag-and-drop questions that check the writing organization. The inclusive learning design supports students with dyslexia who, through the use of visuals, can better comprehend essay writing. At the same time, visual assignments can actually be beneficial for all learners. It is an excellent example of how inclusive teaching and learning strategies can benefit everybody.

A focus on accessibility and the contribution of open educational resources are likewise recurring topics in both the book and in Chryssa’s work over time, as exemplified in the design and delivery of several Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). Currently, Chryssa, with the iPEAR partners, is running a MOOC on inclusive peer learning with augmented reality tools (iPEAR) on the Austrian iMOOX platform. Chryssa is passionate about open online pedagogies: ‘I see myself as a lifelong learner in networked communities online’, she explained to me.

Her experience from multiple international projects in Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL) clearly shows in her book’s pedagogical recommendations. Interested readers can access the first chapter as a free preview on Routledge online – though my favorite is the last chapter, a manifesto for humane technology. An overarching theme that runs through Chryssa’s writing is that she wants technology to be an inviting, inclusive, messy, open space for learning and democracy. What is the secret to effective online learning for lifelong learners that thrive in personal learning networks? According to Chryssa, the critical thing is to connect to a community of practice following democratic and symmetric participation principles as specified in the science of Social Physics. The fact that the two of us are friends without ever having met in person is a beautiful example.

Why did you decide to write this book, and how does it reflect your experience from international edtech projects?

The Pandemic was a blessing in disguise. As Phillip Mirowski (2014) said in his book: ‘Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste’, we need the time to reflect and reimagine pedagogies according to human needs for learning, living and being part of collective intelligence. The turmoil caused by Covid-19 will be felt and debated for years as we seek new possibilities for the educational future and compose alternative scenarios that promote pedagogies of hope, care, justice, and a brighter day (Costello et al., 2020). As educators, we should rethink the roles of education and the pedagogic models better suited to face the reality of the great distance that intersects with intense emotions and misinformation (Peter et al.,2020).

All these Erasmus + projects in higher education (almost ten years) offered the opportunities to work with colleagues from many countries (Norway, Germany, Greece, UK, USA, Spain, Italy, Cyprus, and Ireland, to name a few) and negotiate intellectual outputs from different disciplines, which were extremely helpful in finding out what works and what does not in eLearning courses. I strongly felt that this is the best time to reflect on what I have learned.

What are some practical takeaways for educators?

There are so many things that I would like to share. The first and of utmost importance is to get away from the vicious circle of competition in academia and work collectively and democratically with our colleagues and students. I could not agree more with Pentland (2014, p. ix), who says:

It is not simply the brightest who have the best ideas; it is those who are best at harvesting ideas from others. It is not only the most determined who drive change but those who most fully engage with like-minded people. And it is not wealth or prestige that best motivates people; it is respect and help from peers.

Equally important is to realize that how we are connected describes who we are and what contribution we are willing to make in society. In short, educators need to play a more active role in connecting students and resources and building communities online and offline.

How can we increase cognitive and social presence in online courses?

Social and cognitive presence are interconnected in a networked world that aims to bring people together despite geographical or psychological distances (Tele-proximity). From this perspective, Tele-Social presence (TSp), essential prerequisites are a) communication intimacy in transmedia ecology, b) peer-to-peer learning, and c) fine-tuning the network for energy, engagement, and exploration. In other words, educators and students need to acquire the skill to communicate effectively and usually visually in different media, work collaboratively and build networks that reward engagement and interdisciplinary exploration.

Tele-Cognitive presence is mainly about connecting the dots, reflective praxis and creativity. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel guilty because they didn’t really do it; they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while. That’s because they could connect their experiences and synthesize new things (Pentland 2014).

Thus, by connecting people and resources in networks, educators can promote social proximity and diverse combination of ideas, information or experiences.

What qualities does a teacher need to become a charismatic connector?

The students’ level of autonomy and eLearning maturity (eLearning experiences and digital literacies) indicates how much intervention is needed to get the people to progress, collaborate and share. For example, people from different educational and cultural backgrounds may have experienced more ‘authoritarian’ educators, the so-called ‘sage on the stage’, that control all the course activities and use lectures to reach learning objectives. On the other side of the scale, more experienced students may need less intervention, so the educators could be described as facilitators- the ‘guide on your side’ or ‘fellow travellers’ in network spaces.

The Charismatic connection could be part of students’ journey at every level of autonomy, building communities with social rewards that enhance collaboration. According to Pentland (2012), to build great teams, the charismatic connector (tele-teacher presence) designs activities that offer social network incentives to promote collaboration and need to make sure that:

- Students online talk and listen in equal measure, keeping contributions concise and practical.

- Students face one another, and their conversations and gestures are energetic via synchronous video-enhanced media.

- Students connect directly with one another.

- Students carry on back-channel or side conversations within the team.

- Students periodically break, explore outside the team, and bring information back.

How did you first discover the concept of social physics, and why does it fascinate you?

Research needs transparent data and analysis to make holistic assumptions. Unfortunately, Educational research is underfunded and significantly ignored compared to other disciplines. The investigation of Human dynamics (MIT) and professor Alex (Sandy) Pentland have a large pool of resources, informants and technologies to study human behaviour. What they were able to measure and analyze with wearable devices formulated the basis of Social physics.

To a certain degree, human behaviour is predictable, and we could follow some holistic norms to enhance performance, creativity and collective democracies. Social physics has the potential to improve communication, strengthen engagement, and promote interdisciplinary exploration in eLearning courses. It is fascinating, isn’t it?

In a nutshell, Social physics bridges the emotional, cognitive and physical distance and makes it a privilege. We are the campus, after all (Sowton, 2020).

You devote a chapter to digital wellbeing. Why is it so important?

We all tend to multitask, overthink and get easily distracted by digital notifications. Society suffers from prejudice, polarization and widespread misinformation – the so-called epistemology of deceit. Therefore, digital wellbeing should be an integral part of the learning process to maintain physical and mental health and the wellbeing of society as a whole.

What are the critical aspects of your manifesto for humane technology?

Tristan Harris uses the phrase humane technology to manifest the need for technologies that serve the purposes of learning, living and working in digital environments in harmony with wellbeing and democracy.

More than ever, we need the wisdom to match the power of our God-like technology. Yet, technology is both eroding our ability to make sense of the world and increasing the complexity of the issues we face. The gap between our sense-making ability and issue complexity is what we call the “wisdom gap.”

How do we develop the wisdom we need to responsibly steward our God-like technology? Teleproximity with social physics in education could be a potential answer.

Who should read this book?

The book offers a different perspective on how we connect, learn, and design courses online and offline. It could interest educators, researchers, or instructional designers who are absolutely committed to following innovative teaching methods and technologies. It may be helpful for administrators and policymakers eager to implement influential trends and research into mainstream education to enhance the digital competencies of educators and students in adapting to the volatile circumstances in the job market.

About

Chryssa Themelis is an educational researcher at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway. Her research involves technology-enhanced learning and digital innovation. Her latest book is Pedagogy of Tele-Proximity for eLearning. Bridging the Distance with Social Physics.

Chryssa Themelis is an educational researcher at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway. Her research involves technology-enhanced learning and digital innovation. Her latest book is Pedagogy of Tele-Proximity for eLearning. Bridging the Distance with Social Physics.