Design Thinking: An Interview with Danielle Lake

Danielle Lake is Director of Design Thinking and Associate Professor at Elon University, NC. With a doctorate in philosophy from Michigan State University, Lake’s expertise spans “wicked problem” solving, design thinking and community engagement. Her teaching and scholarship interests bridge Design Thinking and wicked problems research with feminist pragmatism and the scholarship of teaching and learning.

Danielle Lake is Director of Design Thinking and Associate Professor at Elon University, NC. With a doctorate in philosophy from Michigan State University, Lake’s expertise spans “wicked problem” solving, design thinking and community engagement. Her teaching and scholarship interests bridge Design Thinking and wicked problems research with feminist pragmatism and the scholarship of teaching and learning.

For AACE Review we talked about her recent research on design thinking in higher education. The research project analyzed practices and outcomes across 35 courses using an online survey and semi-structured interviews with faculty.

When did you first encounter design thinking and why does the topic fascinate you?

I first encountered DT while writing my dissertation on wicked problems. I was simultaneously designing curriculum intended to bring students and communities together to address situated issues together (food justice, crime and policing, housing, etc.). As a part of these efforts I went through training in intergroup dialogue, strategic doing, and other participatory action practices.

I valued how DT can encourage more relational, embodied and situated learning that encourages iterative and collaborative action.

What shared design thinking practices did you observe across disciplines?

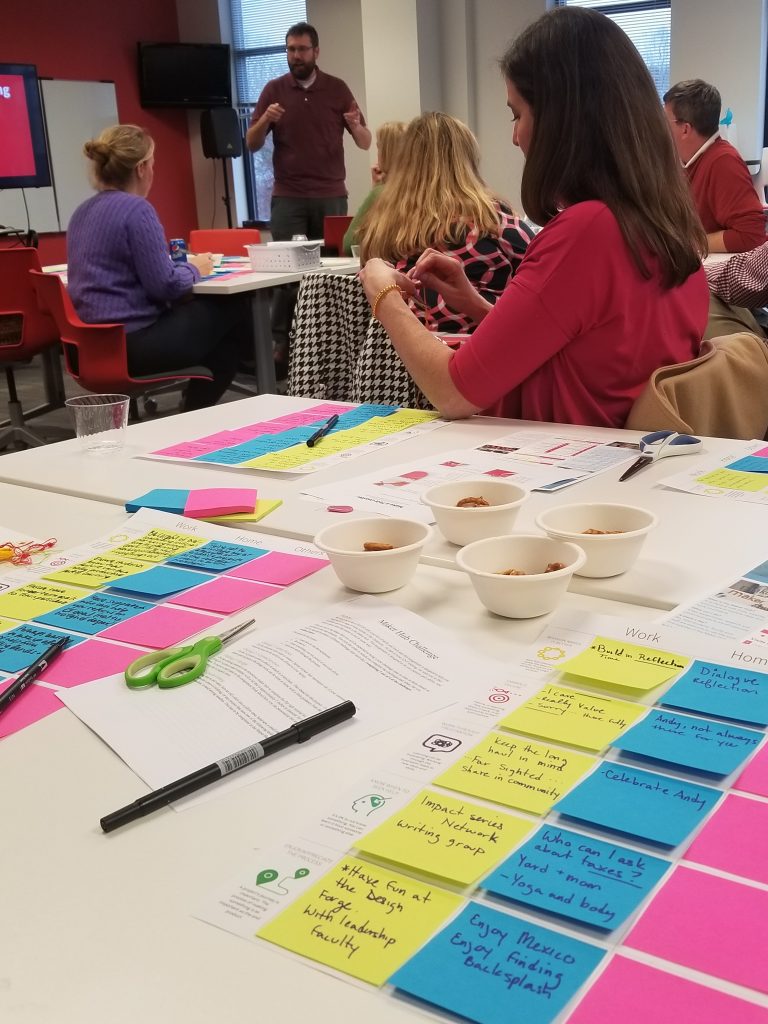

In our study we found that DT is used across disciplines to effectively support high impact learning, especially collaborative project-based curricula. Faculty overwhelmingly felt that these practices helped to build trust on teams and higher quality projects.

Did you observe differences in how different disciplines apply design thinking?

We found that faculty tended to spend more time on the exploratory and imaginative aspects of the process and less time in the embodied prototyping and testing practices. However, faculty with more DT experience tended to provide students with far more making opportunities, requiring early testing of low fidelity prototypes compared to faculty new to DT pedagogies.

In addition, faculty from professional disciplines (like engineering, architecture, and design) were requiring students to engage in far more prototyping and testing than humanities faculty. Faculty from the humanities, on the other hand, provided more support for collaboration, empathetic listening, and ideation. We saw this as a result of university structures and disciplinary blind spots that could be addressed through an interdisciplinary community of practice.

What are typical goals of using design thinking?

The goals for integrating DT are fairly consistent across courses, programs, and disciplines: faculty wanted to provide students with support for creative, genuinely collaborative project-based learning that provided them with skills and experiences valuable for life after graduation.

While faculty had similar aims, the range of DT course projects varied widely from student campaigns supported on-campus mental health, to the creation of marketing materials for off-campus clients, to projects for solving clinical rotation problems found in hospitals, to the creation of an arts-based business plan, to a dream job vision board, to philosophical games designed to played with local community members.

What are risks and limitations of using design thinking from a faculty perspective?

We found it was challenging for faculty across disciplines and experience levels to fully engage students with the DT process in relationship with real world stakeholders. Semester timelines and course hours hamper DT practices such as making, testing, and iterating. We also found consistent barriers to supporting valuable and viable long-term projects, included a lack of training, time, infrastructural support, and access.

We recommend curricular designers consciously create space and time building and sustaining relationships of trust, seeking feedback across systems on course projects, iterating on designs and prototypes, and reflecting on the embodied praxis of the work.

What outcomes do faculty attribute to design thinking?

Overwhelmingly, faculty articulated that these DT pedagogies yielded yield a long list of valued outcomes for their students, including building trust across student teams and increasing the quality of student projects. We are currently in the analysis phase of a second-round study also indicating students deeply valued the process and felt it built important capacities for their personal and professional lives.

This study emphasizes that DT should not be characterized as a quick and easy pedagogical technique that will yield immediate improvements in learning processes and products. Instead, we argue it should be recognized as a flexible method and process for developing the capacities to accept critical feedback, cope with ambiguity, and develop the trust necessary for inclusive and equitable risk-taking.

Your research design had a substantial qualitative component. Did new themes and surprising results emerge from the faculty interviews?

Interviews visualized the shared goals faculty from across disciplines had when seeking out and integrating DT pedagogies into their courses while they simultaneously indicated faculty saw the DT process as synonymous or overlapping with their own disciplinary frameworks.

Interviews encouraged us to create interdisciplinary faculty learning communities. We found that the most highly requested resource was some form of academic support (from building their repertoire of DT practices through easily accessible, curated resources, to learning what others are doing through cross-departmental communities of practice, to more facilitated workshops and consultations).

Are you currently practicing design thinking in remote learning or remote work settings?

Absolutely! It has been a challenge and a joy to offer DT workshops and courses virtually, hybrid, hyFlex, and outside over this past year. We’ve really valued getting the chance to bridge spatial boundaries and bring diverse groups together through these experiences.

What are some of your favorite design thinking techniques?

As a Center for Design Thinking at Elon University, we are most interested in supporting and developing DT processes designed to help us confront and address both our own cognitive biases and systemic oppression in our communities. We’ve really valued the “Equity Centered Field Guide” from Creative Reaction Lab and incredible storywriting and unwriting techniques shared by Josina Vink and others.

Based on your own research results and experience as a practitioner, what research questions and approaches would you like to see to advance our understanding and practice of design thinking?

More mixed methods research examining the merits, limitations, and challenges from across longer time spaces and perspectives is essential (including student, faculty, community, and administrator). In addition, more research exploring the role of emotion and resilience within DT practices is needed.

Cross-institutional and cross-sector comparisons are needed to explore the role of DT in preparing students to address the wicked problems they face ahead.

About

Danielle Lake is the Director of Design Thinking and Associate Professor at Elon University. Her scholarship explores the connections and tensions between wicked problems and the movement towards public engagement within higher education. Her current projects focus on exploring the long-term impact of collaborative, place- and project-based learning, design thinking practices, and pedagogies of resilience. Lake is coeditor of the book series, Higher Education and Civic Democratic Engagement: Exploring Impact, with Peter Lang Publishing. Recent publications can be found at http://works.bepress.com/danielle_lake/

Danielle Lake is the Director of Design Thinking and Associate Professor at Elon University. Her scholarship explores the connections and tensions between wicked problems and the movement towards public engagement within higher education. Her current projects focus on exploring the long-term impact of collaborative, place- and project-based learning, design thinking practices, and pedagogies of resilience. Lake is coeditor of the book series, Higher Education and Civic Democratic Engagement: Exploring Impact, with Peter Lang Publishing. Recent publications can be found at http://works.bepress.com/danielle_lake/

Learn More

Lake, D., Flannery, K. & Kearns, M. A Cross-Disciplines and Cross-Sector Mixed-Methods Examination of Design Thinking Practices and Outcome. Innovative Higher Education (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-020-09539-1